Loliwe

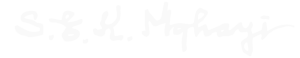

To be sharpened – ukulolwa ingqondo – by life and intellectual commitments: An introduction to S.E.K. Mqhayi

By Sanele kaNtshingana

Samuel Edward Krune Mqhayi (1875-1945) is arguably the most prolific Xhosa writer and historian of his time. It is not only in the quality and quantity that we can measure his contribution but also in the care with which he handled his narratives, his daring attitude that pushed against the grain of both missionary and colonial administration attitudes, his unrelenting truth-speaking and the centering of his people, their experiences, and their philosophies in his work.

Mqhayi’s life was dedicated to the service of his people, usikhonzile isizwe sakhe, and for this, cultural activists, and scholars in the field of humanities and social sciences, in particular, owe him a great deal. He dedicated his life to making sure that young people deeply learn not only their languages but from them too and their histories, iilwimi zabo neembali zabo. He wanted young people to understand that there is power in imagination and in education – not just school education. Mqhayi truly followed the sense his name, Loliwe – which has two meanings. On one hand, the name translates to a “train” and the other implies “being sharpened”. Although he was given the name Loliwe because he was born in 1875 – the year in which steam train was introduced in Cape midland – the Swarkops to Alicedale – Mqhayi embodied the other meaning of being sharpened. ukulolwa ingqondo, to have one’s intellect sharpened by life and intellectual commitment.

Home: the location of Mqhayi’s umbilical intellectual cord

Samuel Edward Krune Mqhayi saw the sun on the first of December in 1875 in Gqumashe, eDikeni (Alice), during a time when Gonya Sandile was in a manhood initiation school, isikolo solwaluko. At this this historic moment, Xhosa-speaking people in the Cape Colony, the present-day Eastern Cape province, along with other Africans located in different geographical areas in southern Africa, had suffered, resisted, and were still struggling with, the terror of colonialism. There had been eight wars of land dispossession that had been fought by Africans against the British colonial forces. In his book, The Founders: The origins of the ANC and the struggle for democracy in South Africa, Andre Odendaal makes a compelling argument that amaXhosa hardly had any bargaining power left after the Nongqawuse cattle movement of the 1850s and were forced to integrate into the Cape economy and society.1Odendaal, Andre. The founders: The origins of the ANC and the struggle for democracy in South Africa. Johannesburg: Jacana Media, 2012. 17-18. Missionary Christianity had reached its peak with mission stations and schools dotted across the African landscape. Many of the Xhosa chiefs who resisted colonial wars had been imprisoned. On the other hand, a new generation of African activists, intellectuals and politicians had been born, and they would later challenge, bargain for power and shape the colonial order in very specific ways. Their ranks included such names as William Wellington Gqoba, John Tengo Jabavu, Richard Kawa, Thomas Maphikela, Isaac Williams Wauchope, and Pixley ka Isaka Seme. This is the context into which Mqhayi was born.

Mqhayi’s father, Ziwani, was umThembu by origin from the Zima clan: ‘uMzima osisithuli othi xa kupha into ngomlomo sele yojiwe ivuthiwe’ (a quiet Zima man who only utters a word after a well-conceived thought) Mqhayi recalls. Ziwani fought in Ngcayichibi’s war in 1879, defending his people who were under colonial attack. Indeed, Mqhayi came from a lineage of people who loved their country fiercely and who were eager to serve and defend their sizwe. His grandfather, Mqhayi, was one of King Ngqika’s closest lieutenants in his inner circle, iphakathi. The life of service and indebtedness to isizwe thus ran deep in Mqhayi. His mother, Qashani the daughter of Bhedle onegama lasemzini (with a marital name), Nomenti, tragically died when Mqhayi was only two and half years old. Both Mqhayi’s parents were Christian converts who at first gave birth to only girls. Because they wanted a boy child so much, they prayed about it. Upon their prayers being answered, they gave him the name Samuel or Samuweli.2Mqhayi critiques this naming system of his parents’ which privileges Hebrew. In his autobiography (Mqhayi waseNtabozuko, 1939) Mqhayi questions the choice of this name. He questions why they did not name him Sicelo or Mcelwa or Celiwe, all of which are Xhosa equivalents of “Samuel”. He admits that his parent’s thought Samuel was an English name because of their lack of understanding. Mqhayi went on to acquire other names as a boy, such as Ngxeke Ngxeke and Loliwe. In his autobiography, Mqhayi explains that he was given the name Ngxeke Ngxeke to denote his not very good looks as a young boy and his exaggerated mouth.3Mqhayi, Samuel Edward Krune. UMqhayi waseNtabozuko. Alice: Lovedale Press, 1939. 30. Mqhayi narrated that over time, he outgrew these names, and that is why they are not used commonly for him.

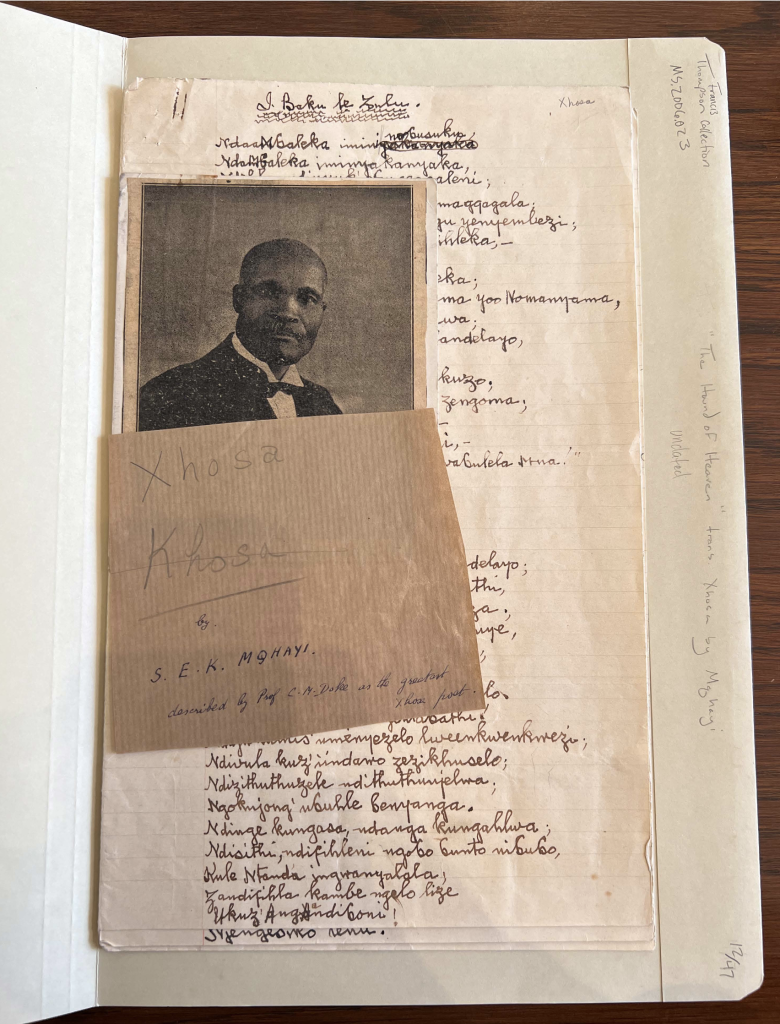

Growing up without a mother in a homestead led by a father who was working as supervisor in railways between eRhini (former Grahamstown and now Makhanda) and eBhofolo (Fort Beaufort) meant that Samuel’s three elder sisters shared the responsibility of raising him. In his autobiography, u-Mqhayi waseNtabozuko published in 1939 by Lovedale Press, Mqhayi recalls how his sister was the first person to buy him a book. Over and above this, Mqhayi’s sisters were central in training and initiating him into the protocols of being a responsible member of his society: ‘…ziyandiyala, ziyandibonisa, ziyandithethisa’ (they advise me, they show me the way, they call me out).

I want to argue strongly for locating inkaba, the umbilical cord, of Mqhayi’s intellectual ideas and world view in his upbringing, in which the role of his sisters’ training was key. This marks a shift from seeing African intellectuals’ ideas as emanating from western institutions such as mission stations, schools, or other educational establishments introduced by missionaries, and later colonial government. Scholars like Xolela Mangcu have demonstrated the importance of tracing the genealogy of African thought in the home and society from which Africans emanate.4See for example: Mangcu, Xolela. Biko: A biography. Cape Town: Tafelberg. 2012. Mangcu, Xolela. “Retracing Nelson Mandela through the Lineage of Black Political Thought.” Transition: An International Review 112 (2013): 101-116. Writing the intellectual biography of Queen Regent Sutu, Nomathamsanqa Tisani, has made a similar argument that the actions and thoughts of Africans like Sutu should be interpreted according to the tenets of the worldview with which they lived.5Tisani, Nomathamsanqa. “A Historical Account of a Queen Mother’s Struggle for Land and Independence of her People.” SADET. Forthcoming Manuscript.

The year 1885, known among amaXhosa as a year of isiTwayi or unyaka weNdlala (year of famine), wreaked havoc in the socio-economic landscape of amaXhosa. Cattle were dying in large numbers because of the disease isiTwayi. In his autobiography Mqhayi recalls the moral decay associated with times of hunger as theft of livestock and robberies of shops increased. This is when Mqhayi moved from Zingqayi to Ngede in Centani to live with his yisekazi (paternal uncle), Nzanzana. Nzanzana was both isibonda (headman) and a leader in the Presbyterian church in Gcalekaland. Mqhayi’s sister, Satyi, remained behind to teach in Lovedale while his father left for Rhini to lead the Presbyterian church there.

Mqhayi spent six years in Centane where he learnt a lot about the Xhosa way of life and isiXhosa discourses. This is where he saw for the first time imidudo yabakhwetha (dances performed by the initiates), amagqirha (diviners) and their practice of ukuvumisa- divination practices, different types of cows which have specific characters and functions, and many other aspects of Xhosa cultural worlds. This way of life, and how justice was administered in iinkundla (courts), inspired him to write his seminal text, Ityala lamawele in 1914.6Mqhayi, U-Mqhayi wase Ntab’ozuko, 46. Ityala lamawele is his best-known work because it was aired on national television in South Africa in the 1990s. It is an adaptation of the play in Ityala lamawele text, which is about dispute between the twin sons of Vuyisile, Babini and Wele. The contention in the story is about ubukhulu, seniority. The whole story revolves around how the case is heard, investigated, and how the ikumkani (the king) arrives to his judgment. This story takes us to the vicissitudes of resolving the dispute among amaXhosa as interpreted by Mqhayi. We also are taken through journeys and the beauty of the cultural life among amaXhosa, including how they host visitors, their dance and music. I grew up watching Mqhayi’s Ityala lamawele on SABC with so much fun with my friends. The most fascinating thing about Ityala lamawele was not so much the legal argument of the storyline but the humor of one of the characters in the play, Phekesa, who had us in stitches in our living rooms in the late 90s. In 2019 a new translation into English by Thokozile Mabeqa – a version of the abridged 1927 school edition – has generated further scholarly interests and appetite.7See for example McDonald, Peter D. “Literary Space/Creative Practice: Reading Ityala Lamawele in English Today.” Current Writing: Text and Reception in Southern Africa 33.1 (2021): 44-49.

Most of his literary works were based on encounters, inspirations, and lessons life taught him in both at home and in school. This was the education he valued the most. In his autobiography, Mqhayi admitted that the education he received in Centane became a cornerstone of his love for his people, more than the ‘book’ education he received in Lovedale. Mqhayi went on to occupy many roles in his career including being a journalist and columnist for different newspapers such as Izwi Labantsundu and Umteteli Wabantu. He also taught at Lovedale and West Bank (kwaNongqongqo) colleges.

The better part of his career was spent being commissioned by different institutions and bodies such as Lovedale Press to write poems, historical narratives, and biographies of abantu besizwe, people of the nation. Mqhayi also composed hymns for his Presbyterian church, and this remains an understudied area of his intellectual contribution. Late in his life he served Nkosi Silimela as a secretary, and this was part of a long lineage of his family serving in leadership positions in his isizwe.

Mqhayi has enjoyed attention from a wide array of scholars in the arts and humanities including Archibald Mzolisa Campbell Jordan, Zithobile Sunshine Qangule, Wandile Kuse, Jeff Opland, Ncedile Saule, Abner Nyamende, Ntosh Mazwi, Antjie Krog, and Sindiwe Magona.8Jordan, Archibald Campbell. Towards an African literature: The emergence of literary form in Xhosa. Vol. 6. Univ of California Press, 1973.; Qangule, Zitobile Sunshine. “A study of theme and technique in the creative works of SEKLN Mqhayi.” Masters Dissertation, University of Cape Town, 1979; Kuse, Wandile Francis. “The form and themes of Mqhayi’s poetry and prose”. PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1977; Opland, Jeff, and S. E. K. Mqhayi. “Two unpublished poems by SEK Mqhayi.” Research in African Literatures 8.1 (1977): 27-53; Saule, Ncedile. “Images of Ubuntu in the essays of SEK Mqhayi in Umteteli Wabantu (1912–1939).” South African Journal of African Languages 18.1 (1998): 10-18.; Mazwi, Ntosh Rose-May. “A critical analysis of Umfi uJonathan Tunyiswa noWilliam Cebani Mtoba as one of the unpublished biographical poems by SEK Mqhayi.” South African Journal of African Languages 34.sup1 (2014): 9-14; Krog, Antjie, and Sindiwe Magona. “Mqhayi’s chapter and verse: Kees van die Kalahari becoming u-Adonisi wasentlango.” Tydskrif vir letterkunde 52.1 (2015): 5-17. A large body of his work has been republished through the collaborative efforts of various African language scholars such as Abner Nyamende, Pamela Maseko, and Peter Mtuze with Jeff Opland.9Mqhayi, S.E.K “Abantu Besizwe: Historical and Biographical Writings, 1902–1944.” Edited by Jeff Opland. Johannesburg: Wits UP, 2009; Mqhayi, S.E.K. “Iziganeko Zesizwe Occasional Poems (1900-1943).” Edited by Jeff Opland. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu Natal Press, 2017.

The published work is only available to those who own these expensive published collections or who have access to libraries that hold the published texts. There are still many of his texts that have not been studied and that are not yet published. The unpublished work is scattered in a variety of different archival repositories. In short, Mqhayi’s work is not readily accessible even as there is growing public interest in Mqhayi, and as his stature and work has taken on a national importance it rightly deserves.

The Five Hundred Year Archive seeks to make his work readily accessible by locating his various texts, including his correspondence and unpublished work, and archiving it online. Wherever possible live links to online versions of his texts occur in this presentation wherever the texts are mentioned. In the wake of fires and other risks that threaten the survival of physical material kept in libraries and archival repositories, the significance and urgency of the digitization approach has never been more relevant.10See Jethro, Duane. “ash: memorializing the 2021 university of cape town library fire.” Material Religion 17.5 (2021): 671-677. I would like us to heed Gqoba’s call to preserve imbali that emanates from the global south because, in Gqoba’s words, “Imbali yakowetu asikuko nokuba ndinga ingaziwa kakuhle ishicilelwe kuba zonke izizwe ezinembali ziba zihleli azifile noko sukuba zezicitakele” (My fervent desire is that our history should be well known and brought into print because all nations who possess a history, even if they are scattered far and wide, continue to live and do not die).11Gqoba, William Wellington. “Isizwe esinembali: Xhosa histories and poetry (1873-1888).” Edited by Jeff Opland, Pamela Maseko and Wandile Kuse. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu Natal Press, 2015.

Umbhumbhiso: the tragedy of Mqhayi’s manuscript Ulwaluko

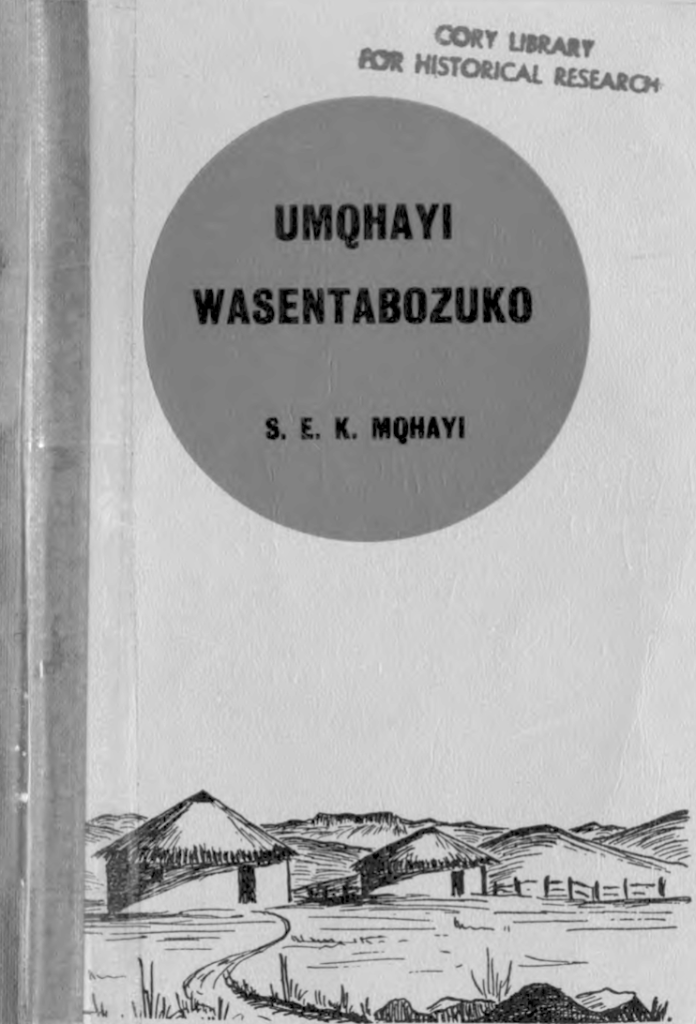

On the 15th of January 1940, Mqhayi wrote to Lovedale’s director of publications, R.H.W Shepherd expressing his intention to submit his manuscript ‘Ulwaluko,’ which he claimed to have written some years previously. At the time of expressing this intention, Mqhayi was updating its orthography and he indicated that he would pay for its printing. ‘How I wish it printed!’ He continued: ‘I shall need three or four pictures of aba Khwetha and Aba Khwetha dance in this one.’ The manuscript was about 100 pages of foolscap paper, and he intended it to have 7-10 pictures, in singles and in groups. A week later, Shepherd acknowledged the letter and indicated that when Mqhayi finished the manuscript and had the pictures he should send them his way. Indeed, the following month Mqhayi submitted the manuscript and on the 22nd of February, Shepherd sent the manuscript to Lovedale’s Xhosa-speaker employed by the press for proof-reading and orthographic tasks, Oldjon, to read the manuscript carefully.12Peires identifies Oldjohn as a Xhosa-speaking reader who was commissioned by Lovedale Press. Oldjon stated that he was anxious to have a full and clear idea of the manuscript’s contents.

Oldjohn’s report is insightful in terms of giving one an idea of what the manuscript was about. ‘Primarily the MS. is a plea in defense of the rite of circumcision. The writer tries to show that circumcision is in itself not so pernicious and immoral as the early missionaries have shown it to be. On the contrary, he regards it as a salutary and dignified national custom…he admits, however, that certain unsavory practices have, through neglect and carelessness, attached themselves to the custom, and it is these practices that degraded the custom in the eyes of foreigners.’

At the heart of the transcript is a discursive response to and criticism of missionaries’ moral high-handedness in relation to the deeming of indigenous practices as evil and unacceptable in the church. Mqhayi was a victim of this attitude when he was expelled from Lovedale for choosing to undergo the ritual of ulwaluko – circumcision according to the Xhosa custom. In this manuscript, Mqhayi defended the ritual, detailing its deep underlying philosophies and how it was conducted from beginning to end. Oldjohn elaborated that ‘the writer shows a thorough grasp of his subject and presents it in a most palatable form. He does not dwell on the surgical aspect of the rite but emphasizes the educative aspect of it- all the privileges, obligations, and responsibilities.’ Oldjohn further remarked that this account and information on the subject was far more extensive than previous accounts by African writers such as T.B Soga and J.H Soga. Mqhayi advanced an argument that the missionaries ‘rejection was futile because most church goers, even some ministers, practice the custom privately.’ He thus made a case for the church to review the question of circumcision. Towards the end, Oldjohn noted that ‘The writer must have taken time and pain to collect and collate such useful information,’ adding that that ‘[N]o Xhosa book that I know contains this information…In my opinion the greater value of the MS lies in the fine description of the rite itself, and the valuable table of chiefs and the corresponding dates of their circumcision.’

Unsatisfied with this review, Shepherd went further and solicited advice from his brother, Peter Shepherd, a white missionary working as a medical doctor. Peter Shepherd responded in April and his views were quite the opposite from Oldjohn’s. His view was that circumcision is done efficiently and effectively medically. To support this, he cited different districts whose chiefs converted to Christianity and had stopped practicing the rite of customary initiation. He acknowledged that ‘[I]t was not circumcision but what is associated with the school that counts.’ Imposing a missionary view, Peter argued ‘if we are to reform such teaching and take it over what form is the “training in manhood” to take?’ He continued, ‘but to announce at present that circumcision should be done wholesale would seem to advocate the obnoxious system of the past, for the Native mind would probably run on the idea that if it should be done, they would prefer it to be done in their own way as in the past.’ Peter Shepherd recommended the Jewish system of circumcision on about the eighth day after birth. In the entire review, there was no single instance where he engaged with Mqhayi’s arguments and their merits and demerits. He missed or neglected the point that the manuscript was not making the case for circumcision but for the value of the educational aspect associated with it, including the lost history of the rite supported by in-depth research.

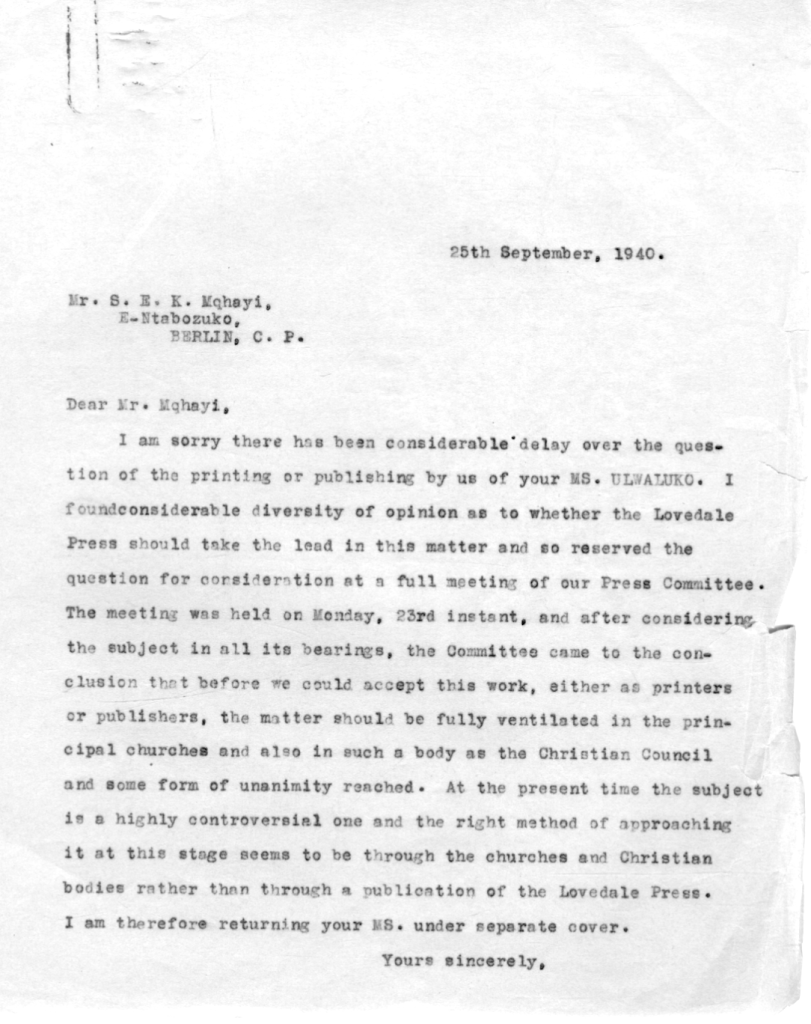

Upon Mqhayi enquiring on the progress of the manuscript, [was the R.H. W.] Shepherd replied that he had taken it to the Press Committee at its first meeting and should be writing soon about the decision. Indeed, in September Shepherd responded to Mqhayi that the committee had considered the matter, and it concluded that before it could accept the work, either as printers or publishers, the matter would have to be fully ventilated in the principal churches and in Christian Council and for some form of unanimity reached because ‘the matter is highly controversial.’ It puzzles me that the institution the manuscript was critiquing would be the very same one that determines the right method of approaching it. The manuscript was returned to Mqhayi, and it never saw the light of the day.

An interview Jeff Opland had with Chief S.M Burns-Ncamashe and G.M Pemba in 1979 reveals possibilities of what could have happened to Mqhayi’s archive that was never published, including the ‘Ulwaluko’ manuscript.13See Peires, Jeffrey. “Lovedale Press: literature for the Bantu revisited.” English in Africa (1980): 71-85. Pemba reported that out of interest in Mqhayi, he visited Ntabozuko after his death to see what was happening to his family. With the permission of Mqhayi’s wife, Tshabo, Pemba found a pile of what he believed to be the last writings of Mqhayi under her bed. ‘The family was using the sheets as toilet paper!’ Pemba narrated. He asked to take the papers with him to safe-keeping, and Tshabo agreed. Tracking his footsteps, S.M Burns-Ncamashe who was teaching at the University of Fort Hare, traced the manuscripts to Pemba’s house and asked Pemba to give him the manuscripts, showing papers that demonstrated that he had permission from Mqhayi’s wife. It appears as if Burns-Ncamashe was doing research on Mqhayi, but it is not clear what happened to the research. To date, no single page of the manuscript has been archived and no trace of a single page of the ‘Ulwaluko’ manuscript is available in the public domain. In a personal conversation I had with Professor Ncedile Saule, he mentioned that he saw a page of the Mqhayi’s manuscript through Ncamashe when he was doing his PhD research on Mqhayi.

There are two lessons from this story I would like to highlight at this point. One is about the censorship that African writers encountered in publishing their materials with publishing houses like Lovedale Press which were controlled by missionaries.14See Mqhayi, 2009, 17-18. This censorship, I want to suggest, contributed to demise of intellectual gems and references that could give us insight into African practices, and the philosophies that underpin them in the face of the deliberate memory erasure inaugurated in the colonial moment. The second lesson I would like to point out concerns limits in the handling of African archival material.

As illustrated from the experience above, African writings went through serious censorship at Lovedale. This was because of the press’s agenda of promoting high moral values of Christianity at the expense of ethical and epistemological values that emanate from Africa. The other issues that frustrated African writers were the inconsistencies of the Xhosa orthography, which was constantly updated, and Lovedale’s stance in avoiding politically charged material. It was not only Mqhayi’s ‘Ulwaluko’ manuscript that suffered this fate, but also the texts of other prominent African writers like L.S.D Raditladi, who wrote the biography of Kgama the Great. Ingqubo Yeminyanya by A.C. Jordan is another text that faced difficulties before it was eventually published in 1940, more than 20 years after it was first written. Jeff Opland notes how uncomfortable Shepherd was with the conclusion of Ingqumbo Yeminyanya and how he had engaged Jordan about the possibility of changing the end. Jordan refused, citing creative license. The white man envisaged an ending that would depict the denigration of African customs, where Western customs prevailed over the belief systems of the AmaMpondomise clan. Shepherd conceded and informed Jordan three months in advance that Lovedale would publish his novel.

We are certainly poorer without the writings that never saw the light of the day. The manner in which the material was handled by Mqhayi’s family presents many complexities that are a result of the unstable and strained relationship between the ‘educated’ and ‘uneducated’ (in the western sense of education) Africans, and perhaps the consciousness of building and preserving an archive amongst the African populace. The lack of sensibility of the importance of keeping and protecting Mqhayi’s archive is precisely because there was no value seen in his papers by the very custodians of his intellectual property. The intentions of Ncamashe who laid his hands on this archive but never preserved it nor made it publicly available are not clear. This is an area that needs further attention in scholarship: of the ethics of the collective African archive. Who gets to have access to this work and to what ends? Who gets to benefit from this work ultimately? To what extent is that a sincere and just project? Or should we choose to be blind to these concerns?

Many scholars working in this area agree that the censorship had devastating consequences in producing histories which were palatable to the missionary sensibilities. I think of this censorship as a form of annihilation, umbhumbiso. I use the concept ‘umbhumbhiso,’ from the verb ‘ukubhubha’ as a metaphor here to signal a sense of loss that leaves one with a deep sense of mourning. This sense of ukubhubha is inspired by an argument that is put forth by Ngxabane to Dingidawo, both characters in A.C Jordan’s Ingqumbo Yeminyanya.15Jordan, Archibald Campbell. Ingqumbo yeminyanya. Alice: Lovedale Press, 1940. It is an argument they make after the protagonist in the book, Nobantu had killed inkwakhwa, considered isinyanya, an ancestor of the Jola clan. Describing the effect of striking and killing a deeply sacred cultural and spiritual symbol that is uMajola, Ngxabane cried that ubhujisiwe, he has been annihilated. ‘No, Jola! You talk of calamities. This is no calamity, for calamities we know. This is worse than calamity. Say, rather, it is the curse of death. For it is the doom, aye, the very annihilation of a people. Who can speak when an entire people has been destroyed? To whom is he to address himself? And how has he survived the general destruction that he is able to speak?’ Jordan likens a person who has been killed in this manner to a mute, who lacks wisdom or words, for the person’s voice and central tenets of their humanity have been taken away. It is in this sense in which I would like to extend this idiom and make an argument that the loss of S.E.K. Mqhayi’s manuscript ‘Ulwaluko’ represented a loss of epic proportions – not only of the physical copies but of intellectual insights which humanise us. It is humanity denied.

Share this:

CREDITS

FHYA would like to acknowledge the commitment of the Cory Library to making their holdings openly accessible and the generosity of their staff in making this presentation possible. Presentation prepared by FHYA in 2023, using materials collected by Sanele kaNtshingana in partnership with Cory Library. Archival curation prepared by Benathi Marufu with assistance from Debra Pryor. Visual curation, page design, and development by Vanessa Chen with assistance from Studio de Greef. Technical support provided by Hussein Suleman. Written content produced by Sanele kaNtshingana and Steven Kotze. Editorial and conceptual support by Carolyn Hamilton. A special project for the development of the isiXhosa components of the presentation was undertaken by Sanele kaNtshingana, Hleze Kunju and Benathi Marufu. Our presentations are archived here. If you wish to make a contribution, use this link.

EMANDULO

EMANDULO is an experimental digital platform, in ongoing development, for engaging with resources pertinent to southern African history before colonialism across what is today eSwatini, KwaZulu-Natal, Lesotho, and the Eastern Cape.