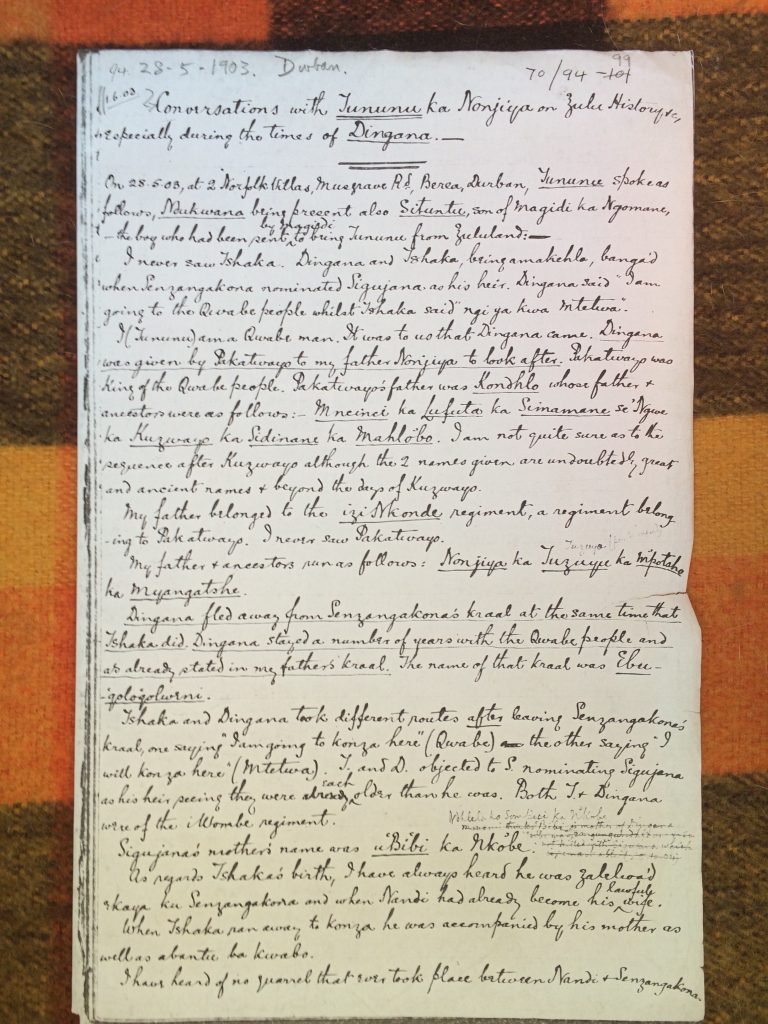

words spoken are written

Meaning can shift when a source is copied, transcribed, translated or annotated (pictured: historian John Wright’s notes visible on his photocopy of a page from Thununu kaNonjiya’s testimony in the James Stuart Papers, Campbell Collections, University of KwaZulu-Natal; photo: John Wright, 2020).

Page into the book

it has a market value

In some contexts archival materials are kept as a collective resource for all of humankind, while in others they come to be traded and privately owned (pictured are two ‘Zulu hoes’ auctioned by Stephan Welz & Co. in 2020 of the same type as archaeological hoes from the Somta Factory hoard, KwaZulu-Natal Museum; photo: Chiara Singh, 2021).

Page into the book

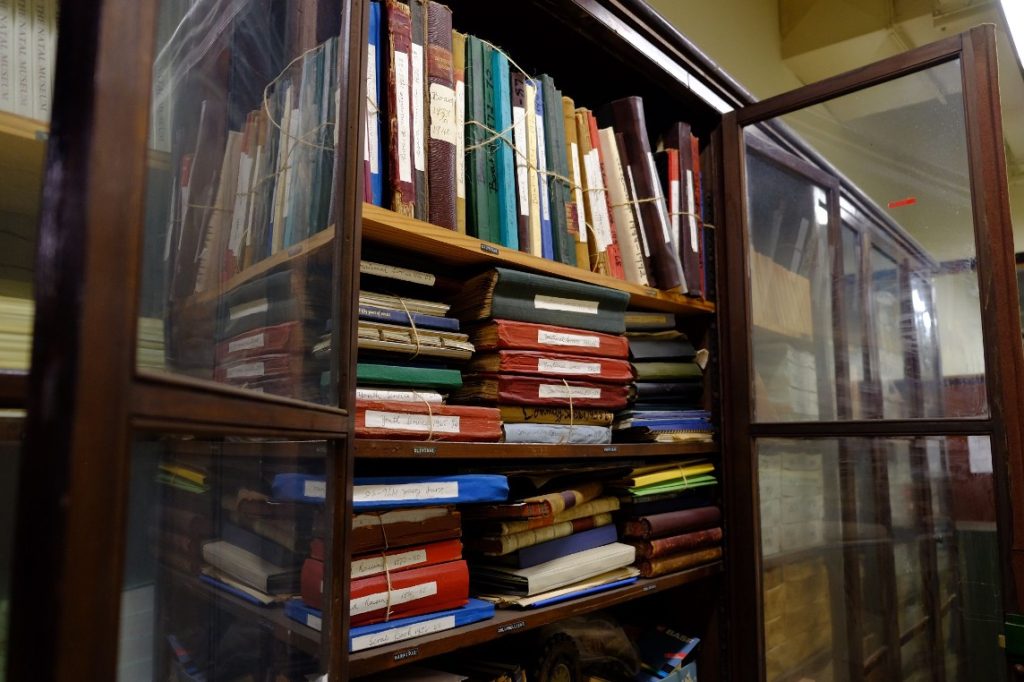

think of an archive

In archival imaginaries, documents that are old and locked away seem to hold the ‘truth’ of what happened in the past (pictured: old files, KwaZulu-Natal Museum Library; photo: Justine Wintjes, 2020).

Page into the book

dwelling, drawing

Drawing can be a useful way of learning about the past. Rock art researchers for example spend long hours creating highly accurate copies of imagery inscribed onto rock surfaces, re-enacting the gestures of the earlier artists (pictured: Paul den Hoed tracing rock paintings at Storm Shelter, Maclear district, Eastern Cape; photo: Geoff Blundell; Rock Art Research Institute & African Rock Art Digital Archive).

Page into the book

discarded

Archival things can follow twisted paths (pictured: a nineteenth-century ‘Kalanga’ pot recently acquired by the KwaZulu-Natal Museum, which was removed illegally from a rock-shelter in Zimbabwe, accidentally discarded by a museum curator and recovered from a trash heap by archaeologist Tom Huffman; photo: Thomas Huffman, 2018).

Page into the book

people keep going back

Focal points in the landscape accumulate traces of human activity over time. Is it reasonable to conclude that the environment, the physical landscape around us in the present, is itself a vast archive that we too form a part of? (Pictured: a rock shelter in the Kho’Khobe valley, Quthing, Lesotho; photo: Justine Wintjes, 2019, with Anton Coetzee and Telang Sekotlo.)

Page into the book

where things end up

Archives are made up of many things that have been transformed and re-purposed (pictured: The Cave House at Masitise, Lesotho, where missionary David-Frédéric Ellenberger once lived, now a museum; photo: Gavin Whitelaw, 2015).

Page into the book

made, formed and polished

Imagining how things once formed part of life – for example how they were made – can help to make sense of archival fragments (pictured are various izicoco (head rings) at different stages of completion in the collections of the KwaZulu-Natal Museum; photo: Justine Wintjes, 2019).

Page into the book

as they live and work

We inherit the archive, but we shape it as well (Dimakatso Tlhoale examining amashoba; photo: Phumulani Madonda, 2016).

Page into the book

on site that day

Archival information can be found in unexpected places (visible in this photograph of a pot dimple at uMgungundlovu, Nkosi Dingane kaSenzangakhona’s capital (1829-1839), is a small smooth stone that may have been used to polish izicoco (head rings), according to one of the workmen archaeologist Tim Maggs spoke to on that day; photo: Tim Maggs, 1973, courtesy of the KwaZulu-Natal Museum).

Page into the book

we do not know

Rock art is an archive bound to the land, yet the world around it has changed fundamentally; we know a lot about it, but there are still many questions (pictured are Masikhanda Maphalala and Jeff Guy discussing painted imagery at uMhwabane Shelter, eBusingatha valley, KwaZulu-Natal; photo: Justine Wintjes, 2010).

Page into the book

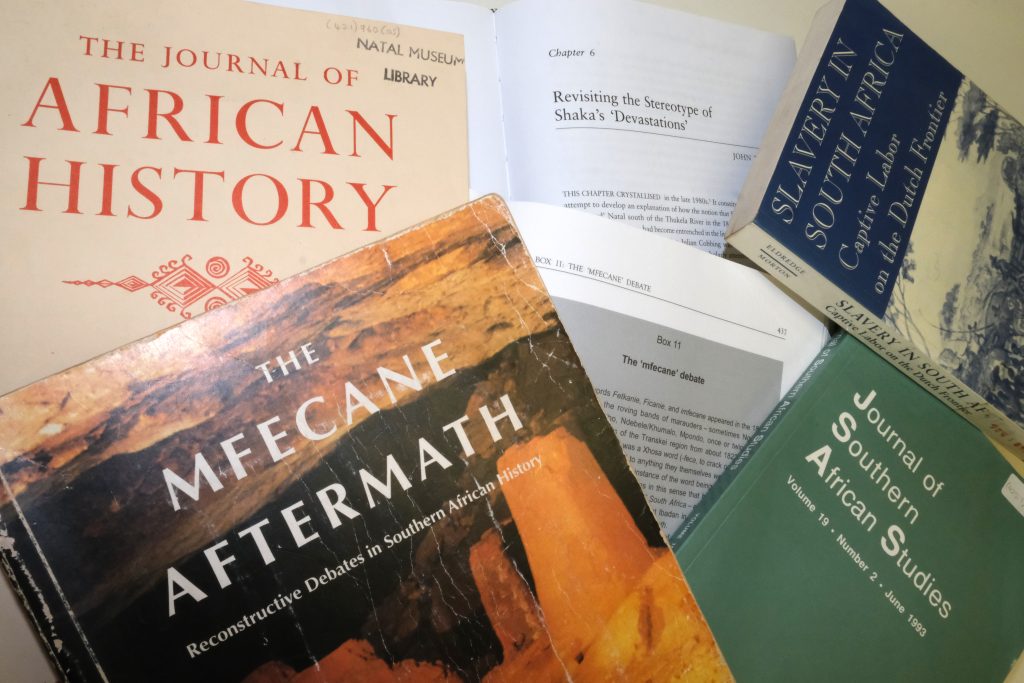

writing and rewriting

Accounts of the past are never truly final or complete, and even good research can be challenged. A seminal 1988 article by Julian Cobbing disrupted earlier understandings of the ‘mfecane’ (a period of social turbulence in south-eastern Africa in the early 1800s) and inspired further debate as well as reflection on the very nature of historical inquiry (pictured: some of the publications involved in this debate; photo: Justine Wintjes, 2021).

Page into the book

never finished

The archive is dusty but it is also dynamic; a site of ongoing experimentation, scholarly and creative (pictured is Thokozani Mhlambi is a musician-musicologist who draws from the deep history of Africa and Europe; photo: John Wright, 2018, Cape Town).

Page into the book

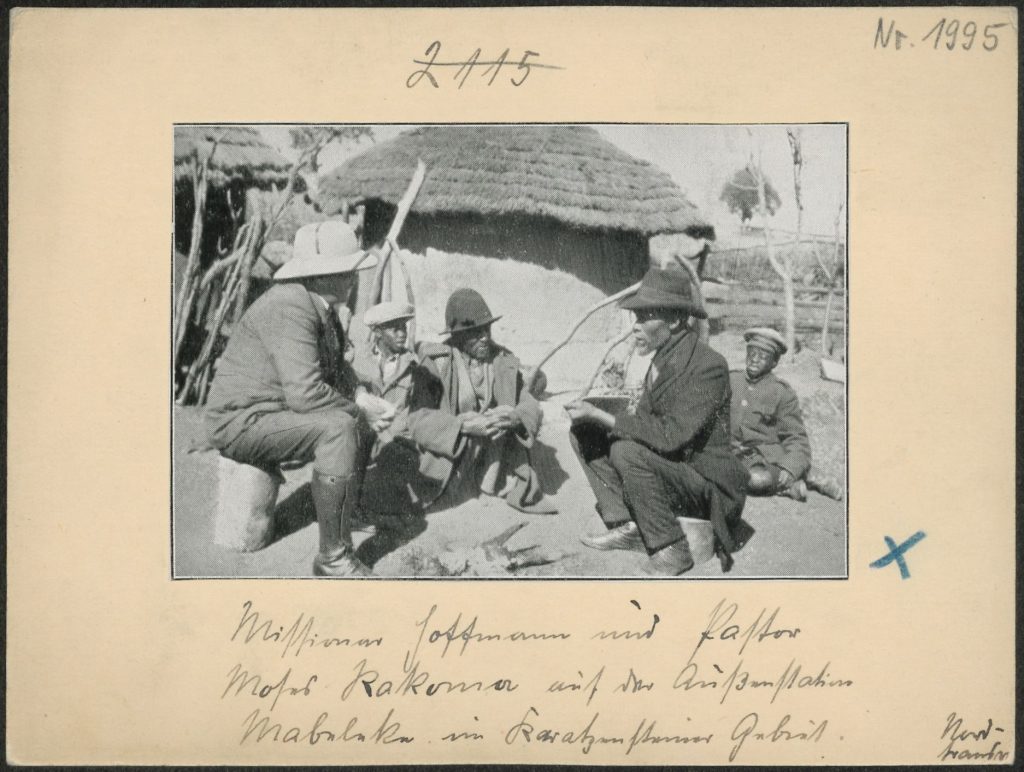

chats, in the past

The archive contains voices but also a lot of gaps and silences. Most words spoken by people leave no physical trace – but some conversations have been recorded (Missionary Carl Hoffmann is pictured here speaking with Pastor M. Rakoma, c. 1920; Berlin Mission Archive, Hoffmann Collection of Cultural Knowledge).

Page into the book

experiencing, processing

Archaeologists learn about the past by digging into the earth (pictured: Mudzunga Munzhedzi and Phumulani Madonda excavating at the Early Iron Age site of Ntshekane, near Muden, KwaZulu-Natal; photo: Larry Owens, 2017, courtesy of the KwaZulu-Natal Museum).

Page into the book

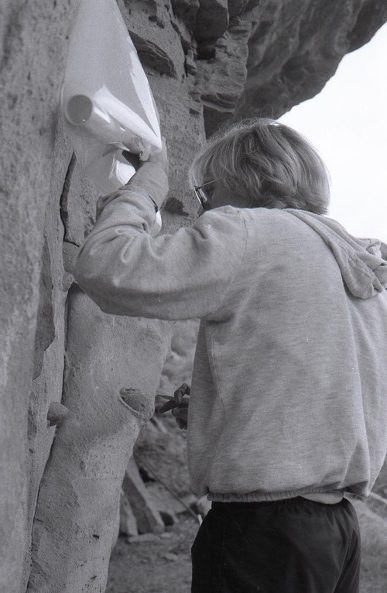

markings they study

Archival materials are recorded in new documents that themselves get archived; copies can come to outlast originals (pictured is Bruce Fordyce, best known for his multiple wins of the Comrades Marathon, tracing rock paintings as a student, Harrismith area, eastern Free State; photo: Gavin Whitelaw, 1982).

Page into the book

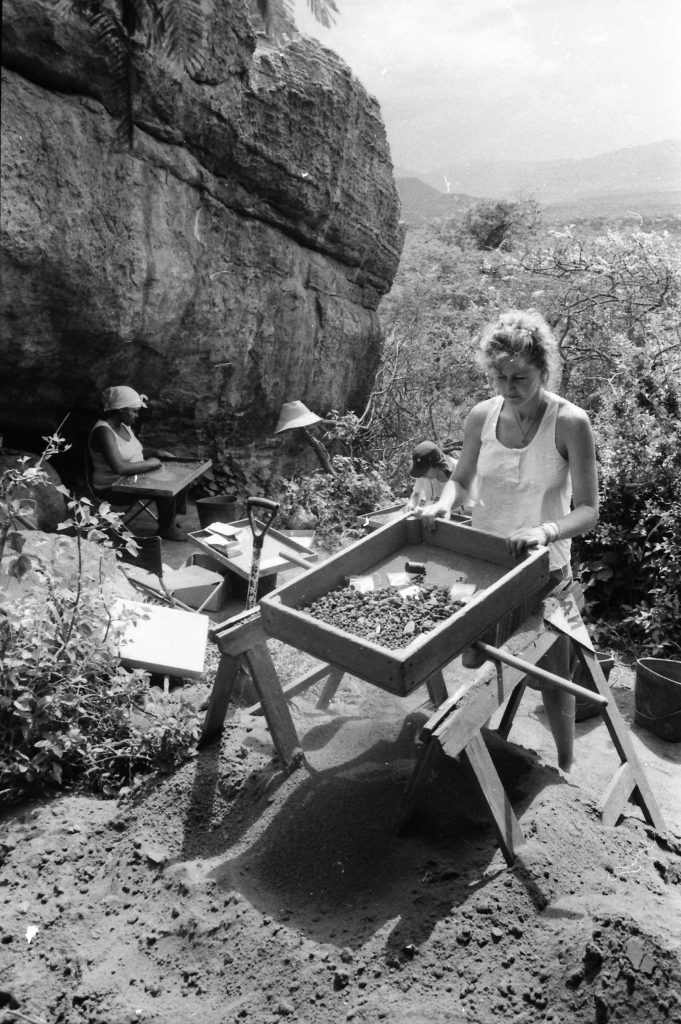

layers laid down

Archaeologists extract significant things from the earth and reconfigure these into another kind of archive (pictured are Ntombifuthi Mkhize (left) and Clare Cresswell sieving and sorting at kwaThwaleyakhe Shelter, near Muden, KwaZulu-Natal; photo: Aron Mazel, 1989).

Page into the book

left behind for others

Images painted or engraved onto rocky outcrops created a sense of place and history in the past and continue to do so in the present (pictured is an engraved rhinoceros at Wildebeest Kuil, near Kimberley, Northern Cape, on land that is currently owned by the !Xun and Khwe communities and a contemporary site of Khoe-San memory; photo: Justine Wintjes, 2019).

Page into the bookVanessa’s Kitchen test post

choose to create

Archives and museums can be started for different reasons by different groups (pictured: one of a growing number of community museums, Marange Community Museum, near Mutare, Zimbabwe, established collaboratively by the Marange community to house both tangible and intangible knowledge; photo: Patricia Chipangura, 2018).

Page into the book

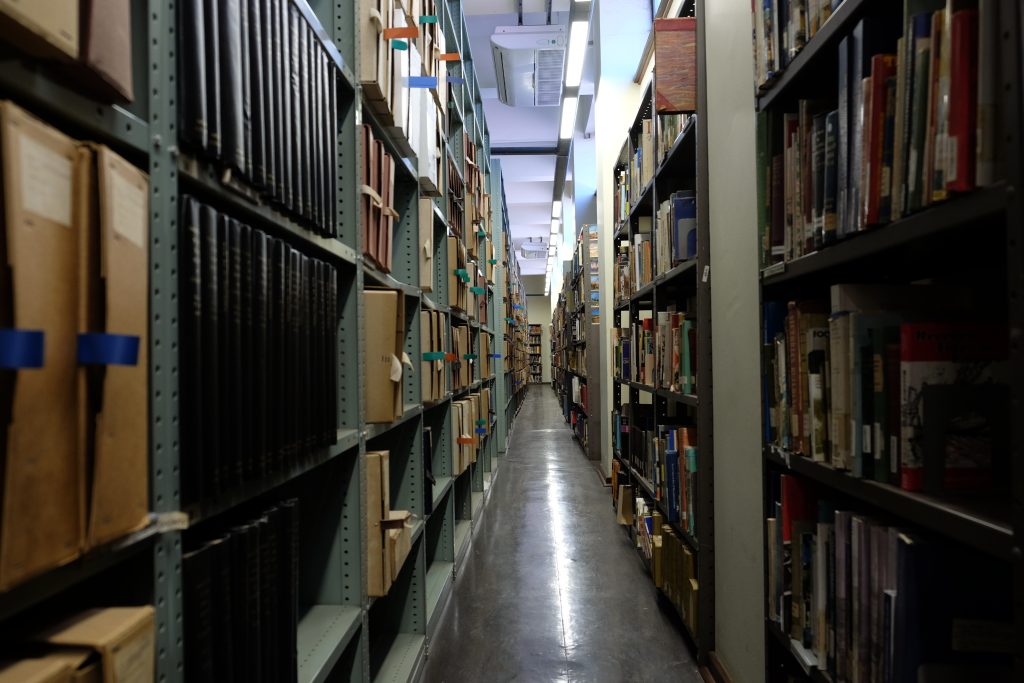

a powerful literary world

Read as much as possible but beware also of the power of text – there is much still to learn from other sources (pictured: the KwaZulu-Natal Museum Library; photo: Justine Wintjes, 2021).

Page into the book

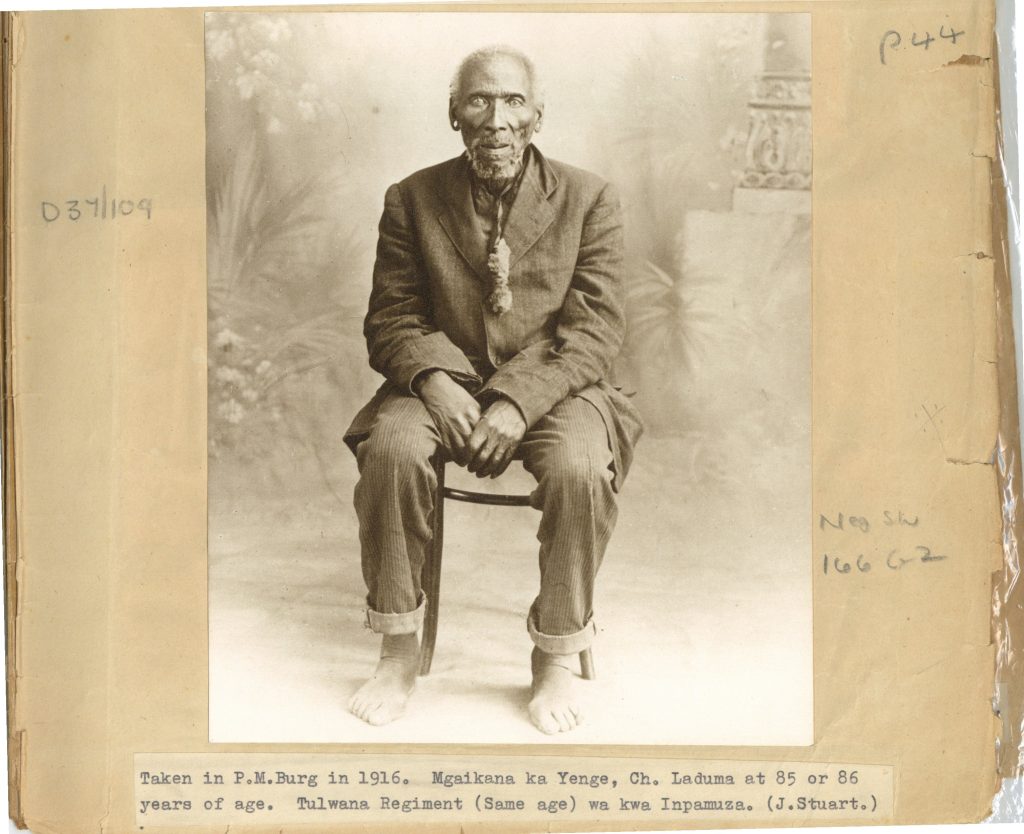

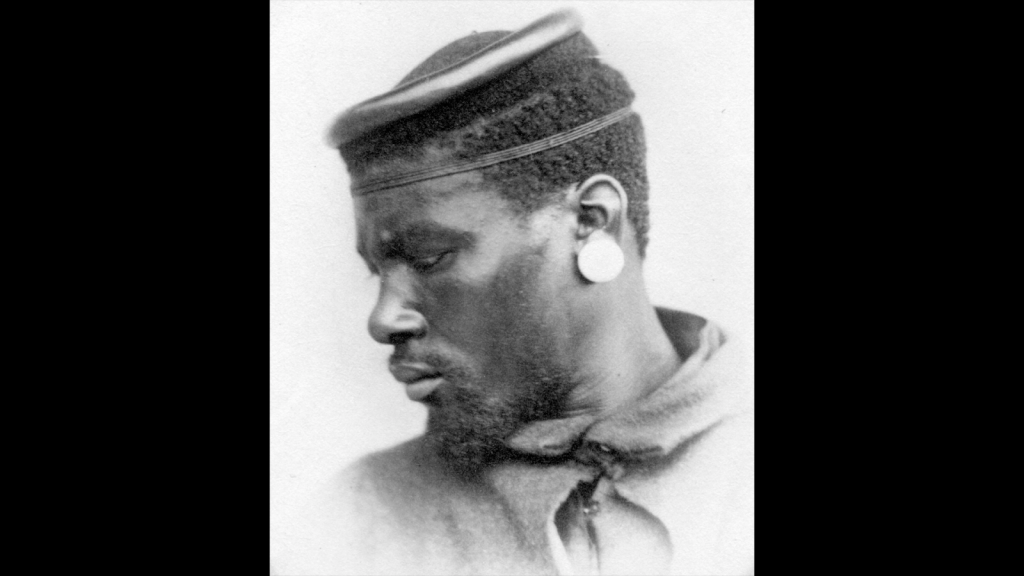

what would he have wanted?

It can feel as though people gaze directly at us from within the archive (pictured is Mqayikana kaYenge of the abakwaMpumuza clan, photographed in Pietermaritzburg in 1916, courtesy of the Campbell Collections, University of KwaZulu-Natal).

Page into the book

thing deliberately kept

For something old to survive, it has to pass through different sets of hands, and successive decisions that it is something worth keeping, even if we don’t always know exactly why (pictured: a gourd beer vessel donated to the Natal Government (now KwaZulu-Natal) Museum in 1904, probably by the well-known Kholwa intellectual Magema Magwaza Fuze; photo: Chiara Singh, 2021, for the Five Hundred Year Archive).

Page into the book

to find buried

Excavated materials are time travellers whose stories are not immediately obvious, and need to be closely scrutinized to shed light on what happened in the past (here Aron Mazel and Jonathan Kaplan examine finds from Umhlatuzana Shelter, near Pinetown, KwaZulu-Natal; photo: Tim Maggs or Val Ward, 1985/6, courtesy of the KwaZulu-Natal Museum).

Page into the book

once worn as symbols

Photographic portraits are visual traces of individual presence as well as collective practice, on the part of both sitter and photographer (pictured: an unidentified man displaying his isicoco (head ring) with an elegant turn of his head; photo: Robert J. Mann, c.1850, courtesy of the Campbell Collections, University of KwaZulu-Natal).

Page into the book

blank or incomplete

The recorded ‘provenance’ of a museum object doesn’t usually include much detail of the original context, such as who made it, who it belonged to, and how it changed hands (pictured: a carved wooden pipe in the KwaZulu-Natal Museum – it was acquired in 1909 as part of a larger ‘Bechuanaland’ collection under the name ‘Handley’ is all that we know; photo: Mudzunga Munzhedzi, 2019).

Page into the book

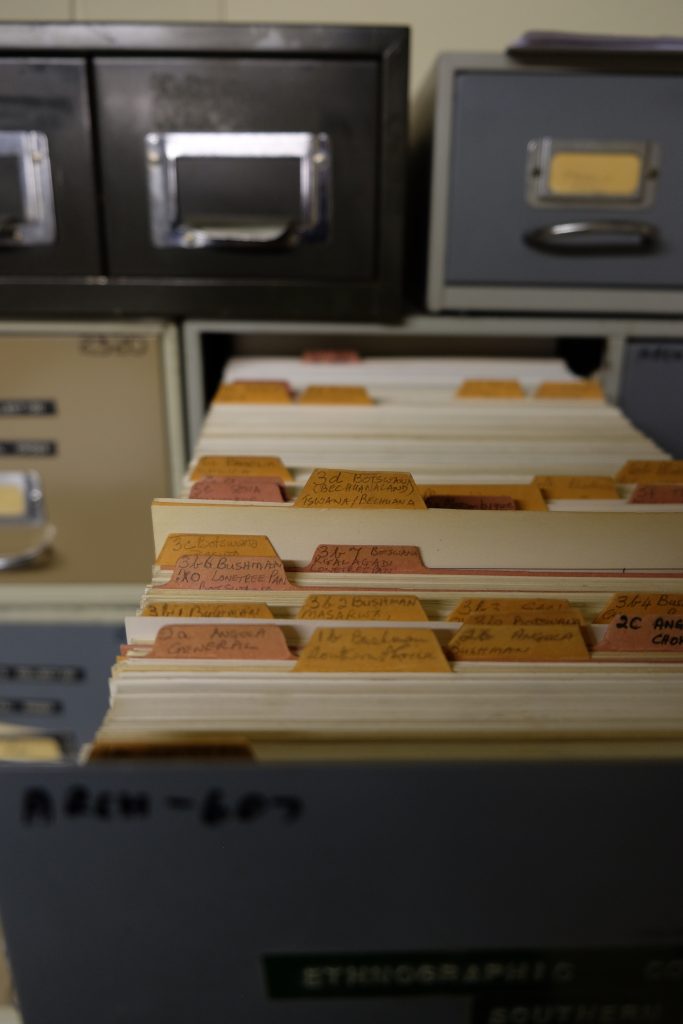

about the transactions

Paper trails can contain a wealth of information but can also be frustratingly incomplete or opaque (pictured: the card catalogue of the anthropology collection of the KwaZulu-Natal Museum; photo: Justine Wintjes, 2019).

Page into the book

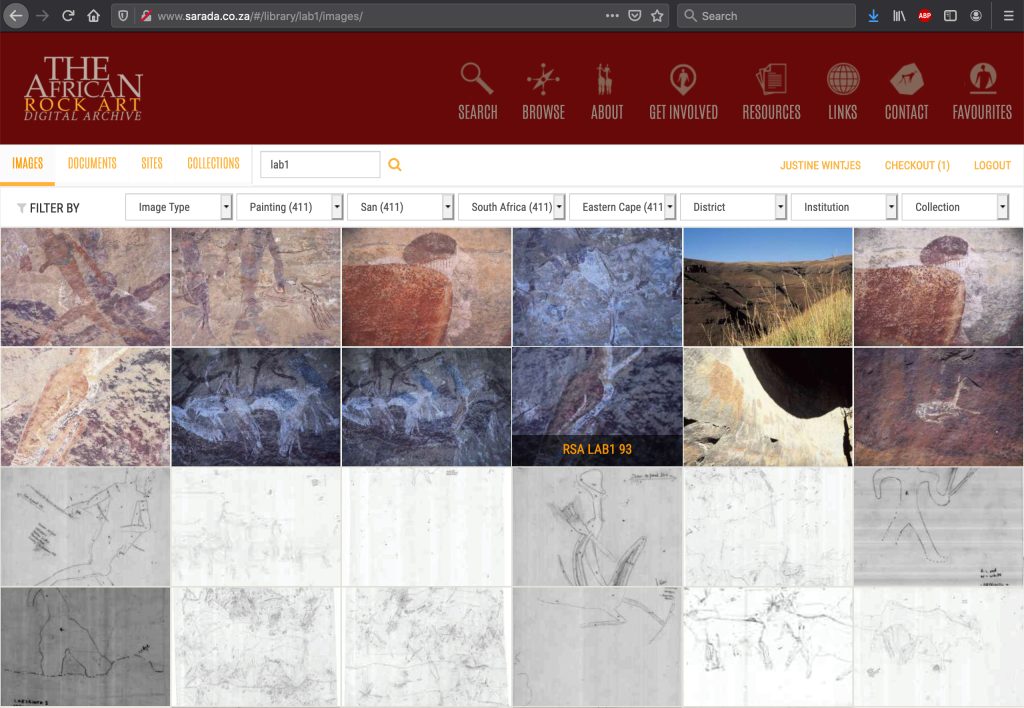

archive that continues

Digital and digitized materials are giving a new presence and longevity to archives. The South African Rock Art Digital Archive is a project that has been running for over two decades. Storm Shelter (near Maclear, Eastern Cape) is one of the many sites that feature in the SARADA digital repository.

Page into the book

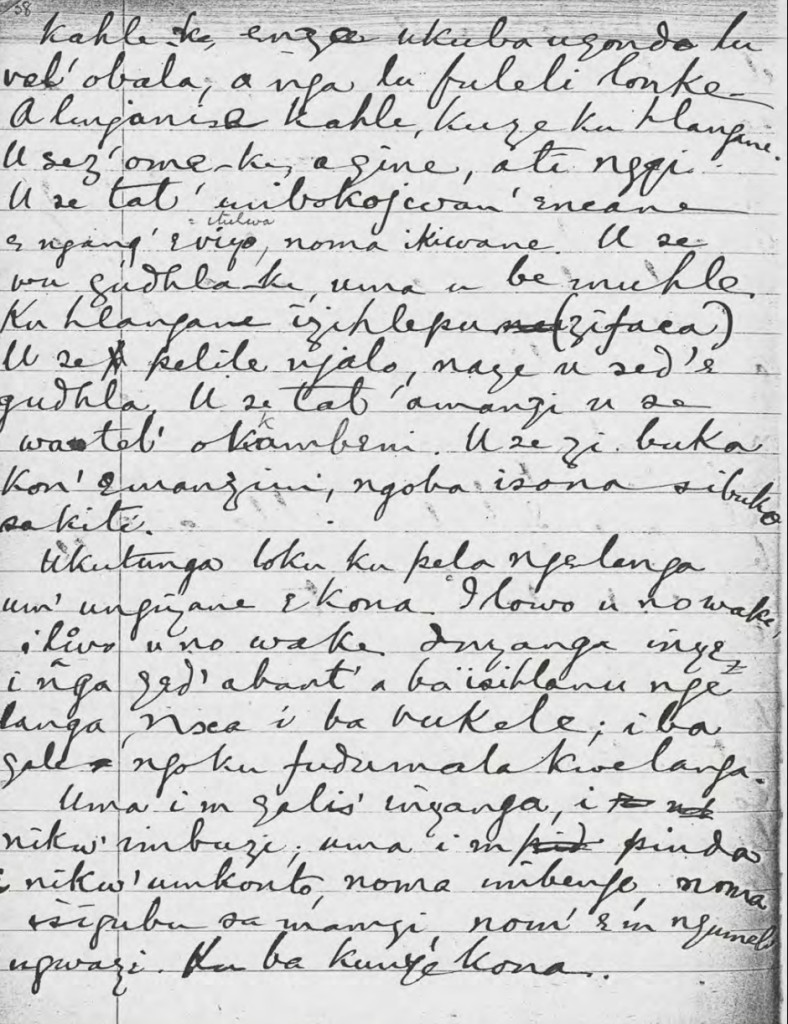

concerning the making of

Even without pictures, archival sources can shed light on creative practices in the past (pictured is Socwatsha kaPhaphu’s testimony in the James Stuart Papers describes the crafting of izicoco (head rings); Campbell Collections, University of KwaZulu-Natal; digital scan of John Wright’s photocopy featured on EMANDULO).

Page into the book

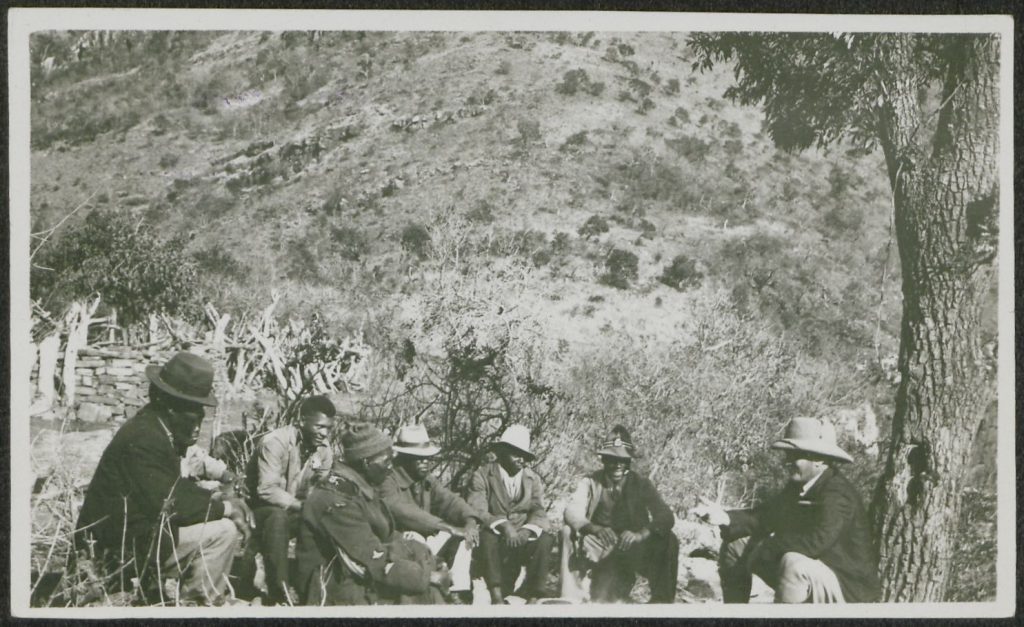

talking and listening

Historical understanding can also come through listening and talking, but spoken words are not neutral either: who is speaking? What are they actually trying to say, and why? How is the conversation recorded? (Pictured: missionary Carl Hoffmann speaking with men in the Wolkberg area, Limpopo Province, c. 1920; Berlin Mission Archive, Hoffmann Collection of Cultural Knowledge.)

Page into the book

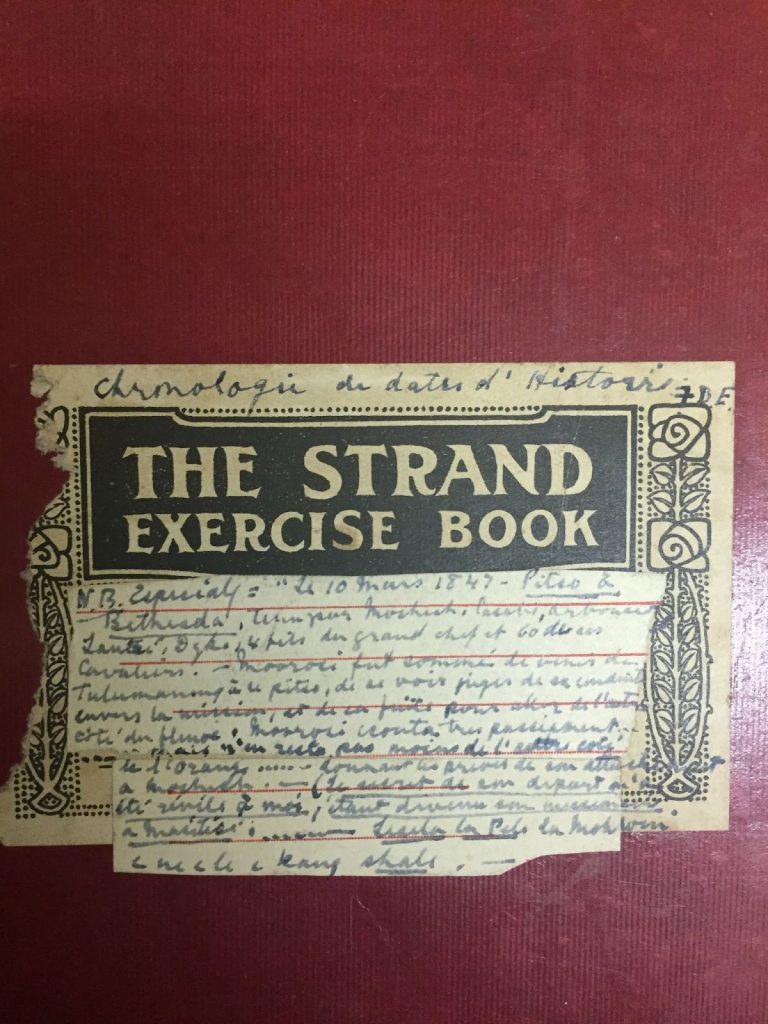

what happened in the past

Written documents are material things that need to be interpreted just as any other source of ‘evidence’ (pictured: notebook in the D.-F. Ellenberger Collection at the Morija Museum and Archives; photo: Rachel King, 2015).

Page into the book

the practice of official record

Official documents are expressions of structures of power, but they can be used in creative and subversive ways (pictured: a map cupboard in the KwaZulu-Natal Museum Library; photo: Justine Wintjes, 2020).

Page into the book

location is meaningful

Sometimes archives contain objects that were designed to be mobile – such as letters or bags – but sometimes, in order to be collectible, objects had to be physically excised from their context, and carry with them traces of this damage and loss (pictured is a rock painting of a lion that once formed part of a large panel at uMhwabane Shelter, eBusingatha valley, KwaZulu-Natal, now housed at the Rock Art Research Institute; photo: Justine Wintjes, 2010).

Page into the book

looking, touching

Understanding the past demands not only reading and writing, but also looking, touching, holding and experiencing (pictured: Chiara Singh photographing a ‘tobacco jar’ among other objects being digitized for the Five Hundred Year Archive; photo: Justine Wintjes, 2021).

Page into the book

together like a puzzle

Over time, most things are discarded, broken and lost, but sometimes it is possible to retrieve them and piece them back together again in creative re-enactments (pictured: Tim Maggs, Val Ward, Aron Mazel and Gugu Mthethwa examining reconstructed pottery recovered during the construction of Inanda Dam, near Durban; photo: photographer unrecorded, mid-1980s, courtesy of the KwaZulu-Natal Museum).

Page into the book

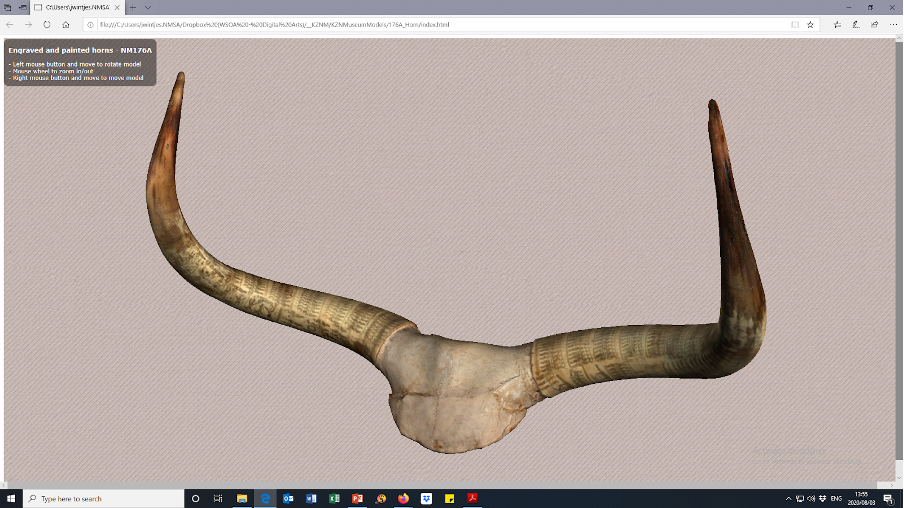

visible in new ways

Digitisation has opened up a vast new archival world inhabited by scans and indexes as well as other novel kinds of archival objects (pictured: screenshots of a digital 3D model of a pair of cattle horns engraved with scenes from the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, KwaZulu-Natal Museum; 3D model: Anton Coetzee, 2018).

Page into the book

structures of power

Archives are shaped by structures of power, but also by chance and the passing of time (pictured: The KwaZulu-Natal Museum in Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal, which houses collections that have been shaped by many different people including collectors, curators and researchers as well as shifting ideological mandates over more than 150 years; photo: Mudzunga Munzhedzi, 2019).

Page into the book

very personal

Sometimes highly personal, intimate belongings end up in archives, sometimes accidentally (pictured: Ghilraen Laue and Dimakatso Tlhoaele examining a suitcase of documents bequeathed to the KwaZulu-Natal Museum after Patricia Vinnicombe died; photo: Justine Wintjes, 2020).

Page into the book

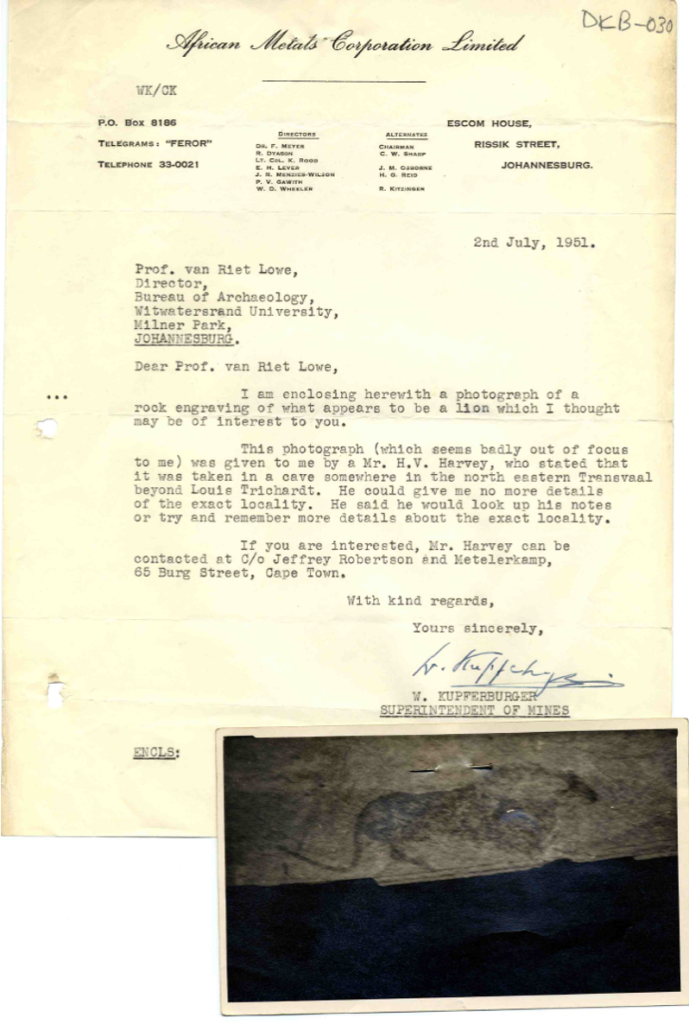

texts can smother

Textual documents appear assertive and authoritative, but they can be misleading (pictured: a letter that gives a wrong location for a rock painting of a lion; Rock Art Research Institute & African Rock Art Digital Archive).

Page into the book

scattered in different places

As time passes, things get mixed up and disappear, and pieces of the past re-emerge randomly in the present (pictured is a small stone artefact salvaged from uMgungundlovu, Nkosi Dingane kaSenzangakhona’s capital (1829-1839), by archaeologist Tim Maggs, during the transformation of the site into an open-air museum by the National Monuments Council in the early 1970s; photo: Justine Wintjes, 2019).

Page into the book

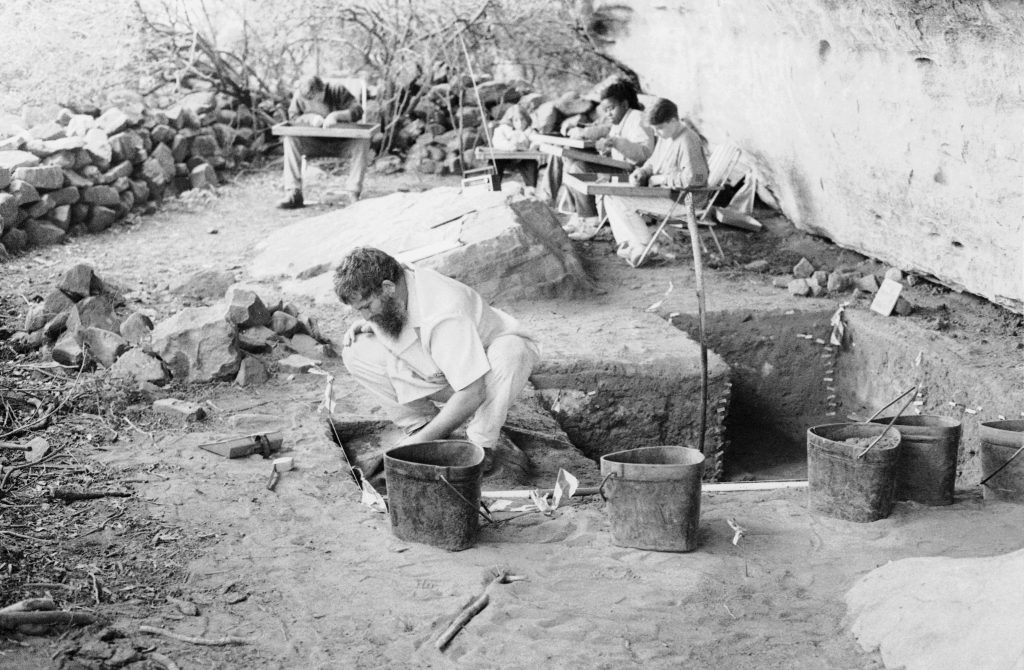

beneath the surface

Archaeological deposits form a kind of subterranean archive requiring a slow, patient labour of discovery (pictured is Aron Mazel and team excavating at Maqonqo Shelter, Mzinyathi valley, near Dundee, KwaZulu-Natal; photo courtesy of Aron Mazel, 1993, photographer unrecorded).

Page into the book